+++

Inner Beauty | Outer Space:

A De-Con-Struc of Crimes of the Future (2022)

A De-Con-Struc of Personal Shopper (2016)

A De-Con-Struc of Snow White (2012)

A De-Con-Struc of JT LeRoy (2018)

A De-Con-Struc of Underwater (2020)

A De-Con-Struc of Jeremiah Terminator LeRoy

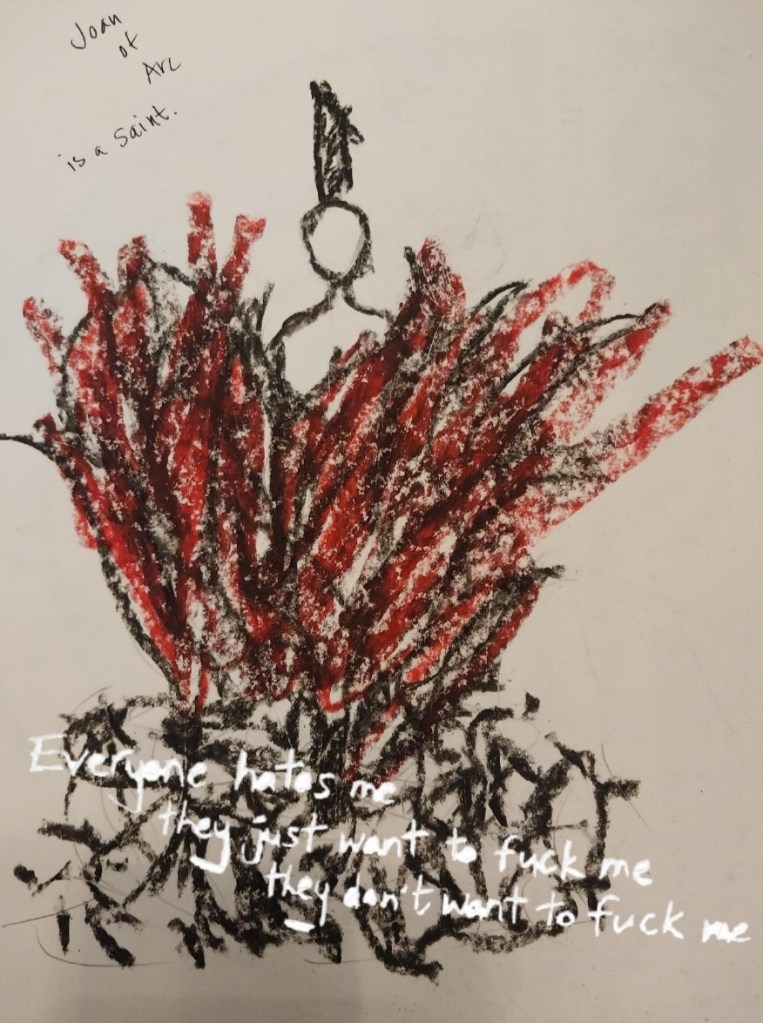

A De-Con-Struc of Joan of Arc

A De-Con-Struc of Seberg (2019)

A De-Con-Struc of Love Lies Bleeding (2024)

A De-Con-Struc of Jean Seberg

A De-Con-Struc of short hair long hair side hair other hair

A De-Con-Struc of who are you how do you feel?

A De-Con-Struc of apathy/ecstasy [as displayed on the face]

A De-Con-Struc of the psyche inside the orange rind

A De-Con-Struc of this list could be endless

A De-Con-struc of I may not stop

A De-Con-Struc of

+

Kristen Stewart is mesmerizing at first sight. Some weird part of me wants to lick her eye makeup off, to embrace her cringe-y shoulders. She moves her mouth too much. She peers from behind, Wippet, her eyes wide as oysters. “That strange little woman. What’s her name? [ snap, snap, snap ] Timlin.” She enforces the rules; she’s also a creep. “Especially creepy,” Caprice affirms.

+

+

For those unfamiliar with the film, Crimes of the Future, written and directed by David Cronenberg, is set in a dystopian world-time in which few people experience physical pain. A cultural fetish has arisen around the mutilation of the body, which is exalted in performance art. As Timlin, our Horatio, explains, “surgery is the new sex.” The story follows artistic duo Saul Tenser, who generates new organs like tumors, and his partner, Caprice, who tattoos and surgically removes Saul’s organs. What’s left of a government system (for whom Saul is apparently some sort of undercover agent) attempts to exert control over a mutating populace who dream of a revolution in which humans eat the synthetic waste they generate.

The unholy trinity of Saul as profane Mother Mary/suffering Baby Jesus/confused pseudo Judas rolled into one is a different essay. The cult of celebrity and the autophagy of the art and entertainment worlds are also different essays. This essay is about boundaries, transformation, and power. It’s about Kristen Stewart letting what’s beneath her surface tremble. It’s about something undeniable seeking to break free. The same sort of trembling manifests in the uncomfortable movements of the Breakfaster chair, in Saul’s hacking and gagging, in the ravenous eyes of the spectators at the sight of flesh sliced open. But nowhere in the film is the awareness of that hunger, its complexities and darknesses and possibilities, more fully present than in Timlin’s pent-up energy. She’s on the verge of spontaneous combustion. WTF is under her skin? She’ll let you glimpse it rippling, but she won’t quite let it out.

+

+

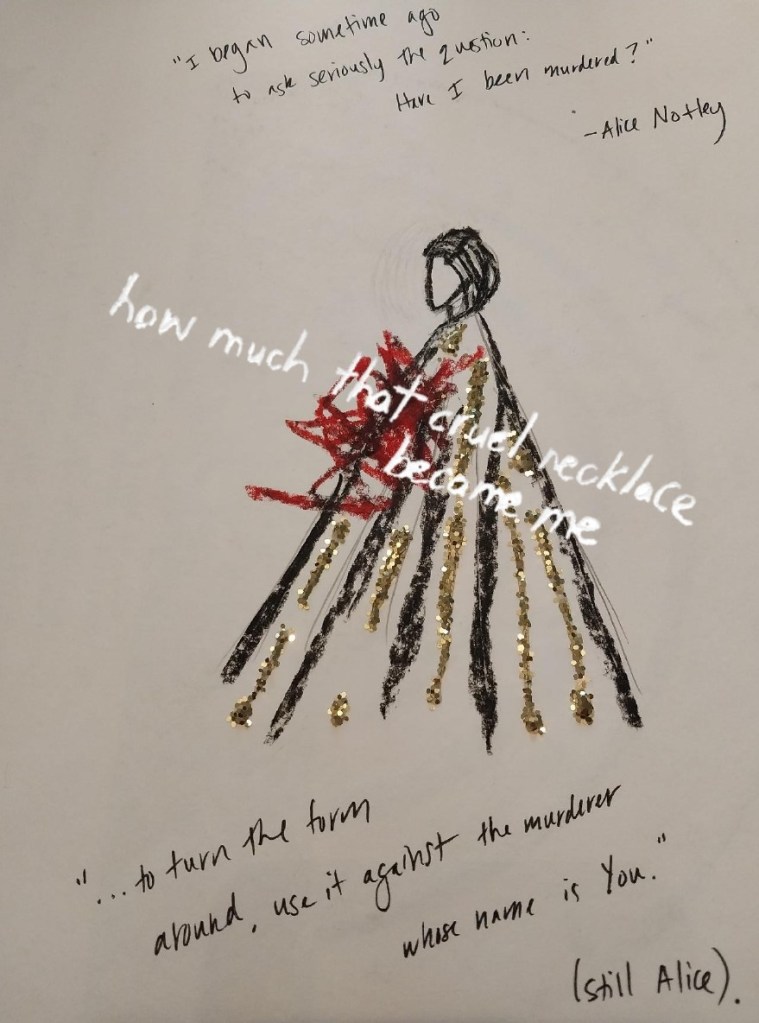

Before writing this essay, I held it in my body for months. I was liminal, and I lived inside liminality. Have you ever been liminal? Of course you have. Do you remember liminality’s seasons, its alternating cycles of numbness and pain? There’s no cute way to write a traditional, academic, patriarchal argument about a mediocre film in that space, and, frankly, doing so doesn’t interest me in the least. I don’t care about your “film opinions” or “critical theory.” I want questions and instability. I want Alice Notley and Joan Retallack. I want a womb. I want to inhabit a space of pure energy. If I stare at Kristen Stewart long enough, will I find a way to break out? Will I find a way to begin to contain myself? Wait, do I want to be OUT or do I want to be IN? Goddamn it if I still don’t know.

This essay is about being open while still containing myself. It’s about wrapping myself in Kristen Stewart and insisting on a collagist’s jazzy kind of fragmentation. It’s about my refusal to edit this essay, which wasn’t originally written for Psycho-Holosuite, by someone else’s rules. I guess, as usual, it’s about compression and expansion, control and release.

+

+

Timlin’s a bureaucrat buttoned up and down in silk. Like, yes the weird part of me also wants to lick her shirt. She’s part of a system, a structure, she’s wrapping the cords of control around her intertwined hands. At the organ registry, she scolds Caprice for bringing a camera into the examination room while, at the same time, she uses her own camera to probe more deeply into the cavity of Saul for a closer look at the goods. Timlin contains desire and restraint, form and chaos in a single vessel. I think what I really want to lick is the internal struggle between those forces, coming up to the surface. The way that, perhaps in spite of herself, Timlin/Stewart follows Samuel Beckett’s insistence that “the form must let the mess in.” Or out. Imagine licking something; you can feel it in your mouth.

In Kristen Stewart’s first moment on-screen in Snow White and the Huntsman (2012) she starts a fire with her breath.

Why am I talking about a WHOLE OTHER MOVIE when we’re already over a page into the essay? Either figure it out, go away, or fucking flow with it. Let it move you.

When Timlin witnesses Saul’s body cut open at the first performance she attends, her eyes sparkle with desire and revulsion. She turns away but she can’t turn away. She might cry. She hides her face behind Wippet again.

After the performance, Timlin won’t let Wippet touch the Sarc, but she makes her own admissions to Saul about the sexual nature of the surgery. “Do you mind if I ask you something intimate?” Buttoned again in that silk I crave. “I wanted you cutting into me. That’s when I knew.” Buttons are for concealing. They’re also for undoing. Pleasure and pain inherently cross boundaries. I know what desire is because I place myself inside your flesh; I transpose our experiences. I see you open and I want you to open me.

+

+

“Your psychological boundary is to your psyche what your skin is to your body. It’s where you end and the world begins. And just like your skin it has two functions: it contains you and it protects you. Imagine your psychic skin being like an orange rind. Like the covering of an orange, your psychological boundary has an inside and an outside: The outside, protective part of the boundary shields you from the world; the inside, containing part shields the world from you.” (The New Rules of Marriage by Terrence Real, 2008)

There’s power in a rind. When being questioned by Detective Cope, Timlin/Stewart’s lips move like she wants to say more. What she admires about Saul is that he seizes control “of the rebellion of his own body.” She can’t stand the detective touching the diagrams of Saul’s organs overlaid with tattoos. She moves. She hesitates. She clasps her hands together in a movement that’s simultaneously restraint and caress. It’s what she controls that’s compelling. It’s what she can’t resist allowing through. She telegraphs her impulses, even while holding them at bay.

When she has Saul alone in a cramped office at the organ registry, she moves into his space. She pushes him across the entirety of the room. Her desire is a black hole, an accretion disk, an event horizon. She gasps, begins to speak, but doesn’t. “I almost…but I didn’t.” She’s a nervous system. “That is where I live.” Her eyes well. A tear falls. She examines his mouth before kissing it. She’s a singularity. A force. Inner beauty | outer space.

“No desire if it’s not forbidden.” (Personal Shopper, 2016)

In Kristen Stewart’s first moment on-screen in Seberg (2019) she starts a fire with her breath.

+

+

They’re starting her on fire. They actually started Jean Seberg ON FIRE. Jean Seberg is in the body of Joan of Arc, being burned at the stake while pretending to be burned at the stake. Kristen Stewart is in the body of Jean Seberg who is in the body of Joan of Arc, pretending to be burned at the stake while being burned at the stake while pretending to be burned at the stake. They set her on fire. Who’s they? You’re they.

Last fall, as I was drafting most of what you’re currently reading, as I thought about what I wanted and what I didn’t, what I wanted to reveal and what I didn’t, I watched and watched and watched Kristen Stewart. I lived in her twitches and hesitations, in her stutters and gaps, in the void between what she says and what she doesn’t. I lived beside Timlin and her split/mask precursors. In Personal Shopper, Stewart’s Maureen puts on someone else’s dress and becomes a prism. “Radiance and resurrection.” She’s also Maureen’s twin brother, Lewis–otherwise absent in death–present in the carriage of Stewart’s shoulders and the husk of her voice. She wants to be someone else. But she doesn’t know who.

In JT LeRoy (2019) Stewart binds her breasts, “turning into someone else,” looking fucking feral in a mask, shattering when the mask comes off, giving body to what is bodiless. “This is all I am.” “You go in further to get out,” intones Laura Dern, in the same drawl she uses in Inland Empire to talk to an interviewer in a filthy interrogation room.

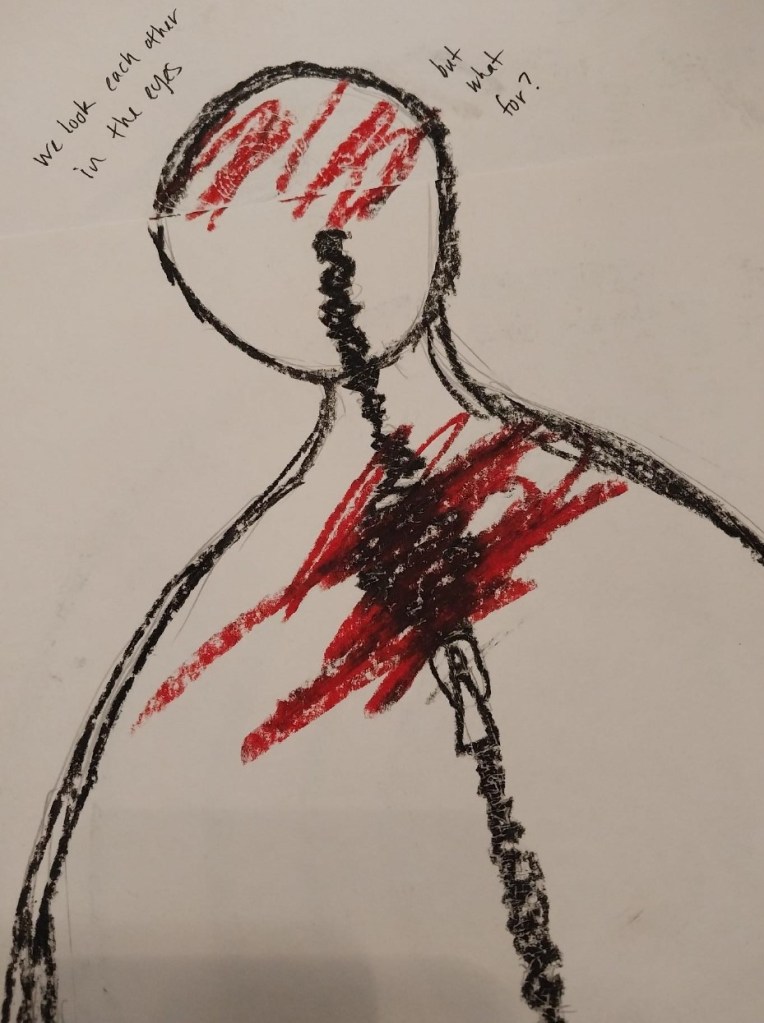

“We look each other in the eyes but what for?” (Breathless 1960).

Like, yes, I watched Breathless too, so I could measure Seberg’s Seberg against Stewart’s Seberg against Seberg’s Joan of Arc against Stewart’s Seberg’s Joan of Arc.

I’ll say it again: We look each other in the eyes but what for?

“A desire to be open,” says the performance artist Odile, who mutilates her face, inspiring Caprice to do the same, “is often the beginning of something exciting, new.” In case you’re lost, we’re back in Crimes now.

Joan of Arc is a saint. They set Joan of Arc on fire.

“It’s a very dangerous form to be in.”

+

+

There might be a mutilated shadow version of this essay. There might be several. This might be the only version.

“Containment means your capacity for restraint. The containing part of your psychological boundary (the inside of the rind) stops you from leaking your ‘stuff’ out onto those around you–your rage, your anxiety, your sexuality, your certainties about being right and wrong. It stops you from acting out your inappropriate impulses.” (The New Rules of Marriage)

+

+

Perhaps I’m fascinated by Timlin’s rind because I struggle to maintain one. Or do I? Maybe it’s your rind that’s fucked. Around the time I’m being asked to re-shape this essay, and refusing, another editor of another place (neither of which are Psycho-Holosuite) asks me to write a piece of content for his journal. When I decline, politely and simply, he responds “cold as ice.” When he asks me to use my time to create something totally new, for free, for his benefit, this person has no idea what’s happening in my life. He can’t possibly understand how that life is coming apart in my hands, how I’m feeding demons the moth-eaten threads, to sate them, how I’m examining the other threads, the ones with strength and give, for a future I hope is there, how I’m pulling at shiny pieces of Kristen Stewart to weave something new, something knifeproof, something that is maybe also a knife.

“I will become your weapon.” (Snow White and the Huntsman)

If a male writer politely and simply declines a request, does a male editor say to him “cold as ice, bro”? When I say no, I mean no. Sometimes, in my head, I think “fuck all of you.” Fuck all of you besides Oli Johns.

“You can’t have my heart.” (Snow White and the Huntsman)

“Autopsia means seeing for oneself.”

“Worth the risk,” Timlin says, so she can see her own handiwork at the autopsy performance at the end of Crimes. She watches Wippet’s face for a reaction while snuffing hers out.

I’m not particularly moved by the film or its cultural and historical contexts–which, because I’m a woman, as a rule, don’t include me, not as I see myself–beyond Stewart’s strange and enthralling performance. The story is disorganized at best and over-relies on exposition by way of the rather convenient and otherwise extraneous Detective Cope. Viggo Mortensen carries Saul Tenser inconsistently depending on whether he’s in ninja garb (flapping his sleeves around, ready to be a pageant girl) or not. Scott Speedman’s performance as Lang is wooden and awkward. And my dear Caprice, as the poets know, chaos is unmappable.

What if a corpse is just a corpse?

In the end, Timlin simultaneously leads two audiences to an edge where she defiles a miracle. She counterfeits an inner world. She attempts to halt the undeniable transmutation of the body. This is where Stewart and Timlin part ways.

What glimmers in Crimes is Stewart, mantled in another’s skin, suffusing an undead suit with smoldering heat. She becomes light, becomes the pressure under which her own frame might collapse. It’s this sort of embodied transcendence that interests me. What’s the point of entropy if it denies what’s possible? Stewart doesn’t defile a miracle, she is the miracle. Her performance holds the hope that even if we’ve inherited a toxic world, we can choose and wield the energy we radiate. That sort of combustion is worth the risk.

+++

Crimes of the Future is out there right now, as is Kristen Stewart.

+++

Danika Stegeman’s second book, Ablation, was released by 11:11 Press November 1st, 2023. Her first book, Pilot (2020), was published by Spork Press. She’s a 2023 recipient of a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund. She’s an assistant editor for Conduit and does light bookkeeping for Fonograf Editions. Along with Jace Brittain, she co-curates the virtual collaborative reading series It’s Copperhead Season. Her website is danikastegeman.com.

Note: both Ablation and Pilot have their own de-con-struc here and here – Danika is the only writer so far to receive such a “honour”, that’s how special she is.

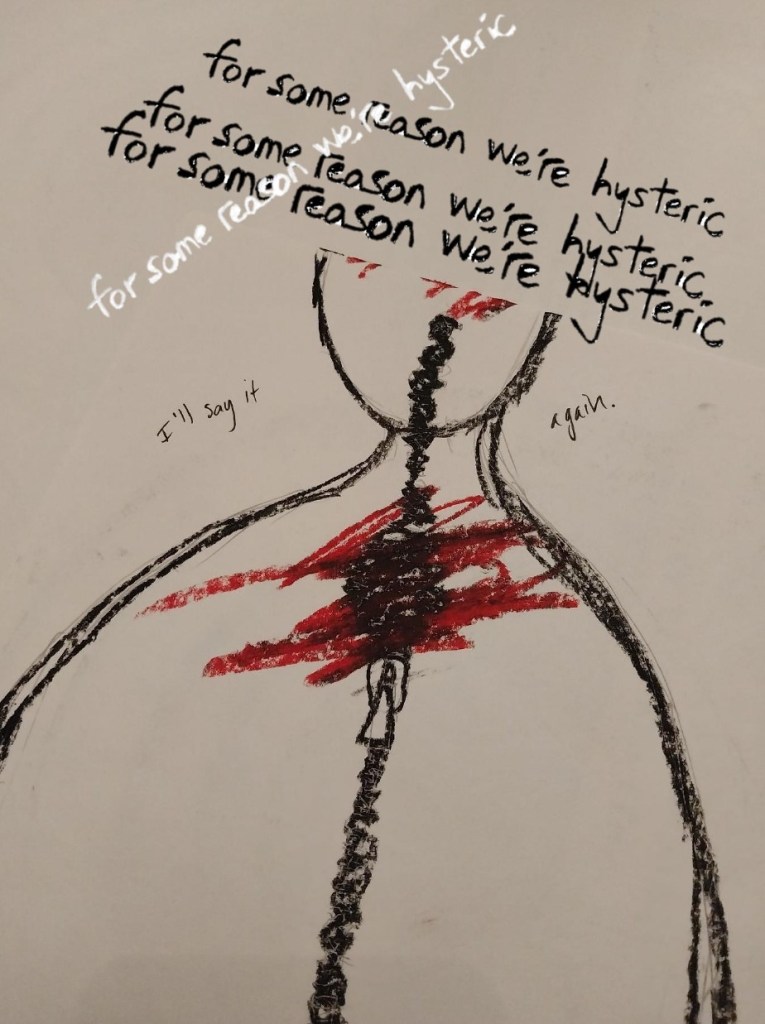

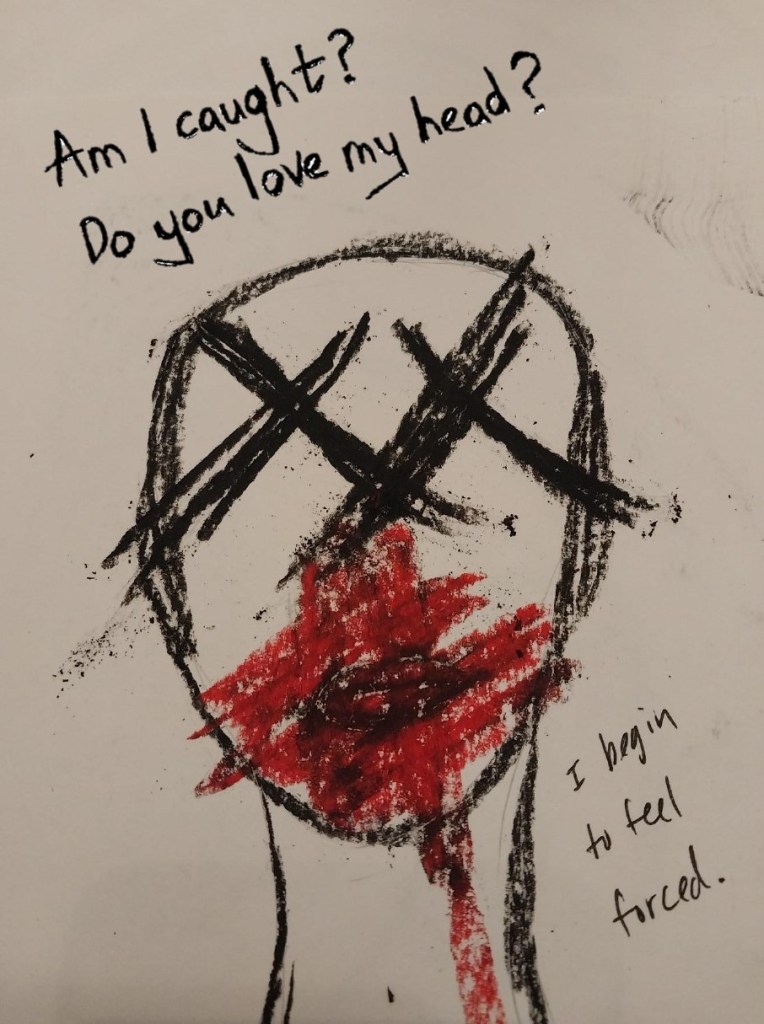

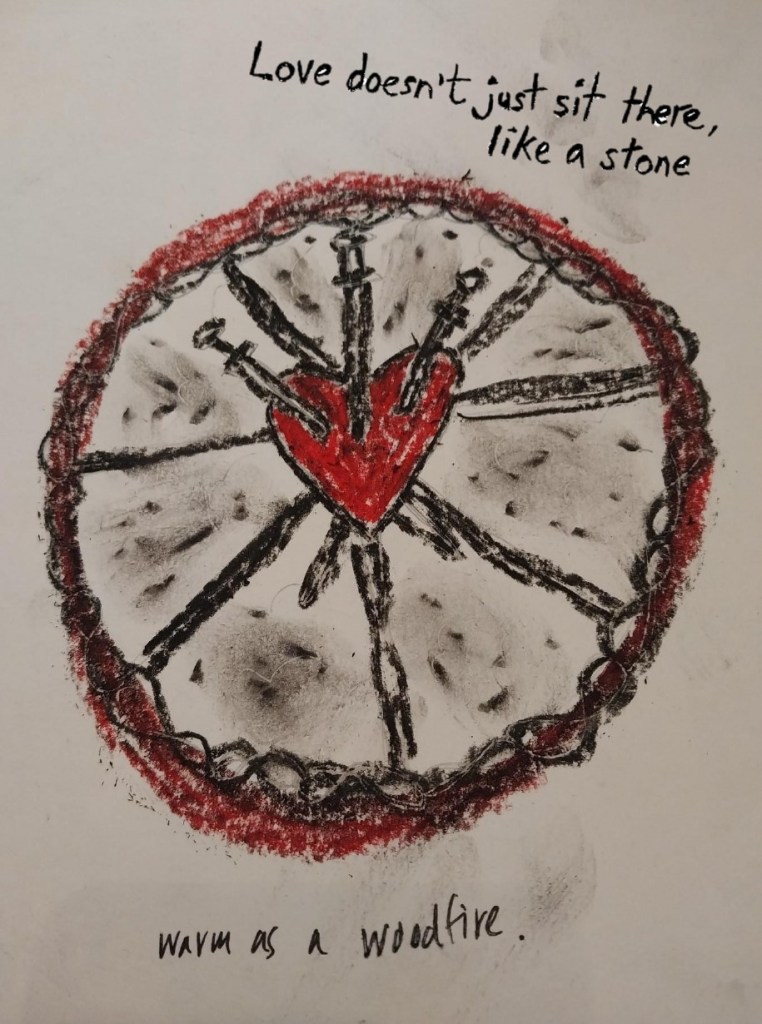

There’s also the de-con-struc she guest-wrote about Casket Flare, and her film dada piece on Midsommar, and a general creative aura around the site that makes you feel that she’s both inside of and along the ley lines of everything e.g. she taught me how to do a cento, and pretended that the four images below look like Kristen Stewart.

+++