+++

Title: Cronopios and Famas

Author: Julio Cortázar

Premise: Life is tough and surrealism isn’t.

Publisher: Pantheon Books

+++

Ever seen Blow Up?

That was Cortázar.

Blow Out?

In an alternate reality, also Cortázar, only at the end John Lithgow is holding a piece of card that says knife on it and Nancy Allen is dressed in the Robocop suit and John Travolta is delirious, sees Brad Davis’s dick in the cracks of the bug-ridden bedframe.

+

There’s no easy way for me to ground this thing without first reading Wikipedia and I don’t want to do that so I’m gonna go from memory and guesswork.

Cortázar was an Argentinian writer who lived in other countries for most of his life and wasn’t Borges. There’s a pic of him posing with a cigarette in his mouth on one of his book jackets.

Does any of this matter?

Yes, it really does, in terms of surrealism and what it represents to the person utilising its cloaking powers. I use surrealism too. But I wasn’t alive between two world wars. Neither was Cortázar as far as I know. Does surrealism hide the user? Is that what they wanted?

+

Not Wikipedia, but the inside cover of Cronopios and Famas says absolutely nothing about the author. That’s weird. Perhaps they forgot to put it in?

The original publishing date of this book is 1962. I assume Cortázar was over thirty when he wrote this, which means he was a teenager when World War 2 broke out. But that war wasn’t so important for Argentinians. The junta that came later is what he would’ve been hiding from. If he truly was hiding?

Surrealism is a way of coping, not just with the horrors of the world, but your own lack of a leading role in either stopping or perpetrating them. Usually the former for writers, but not always. Celine springs to mind. Was he still a Nazi fan during World War 2? Can’t remember. I’ll have to check wiki for that.

+

I wasn’t going to write anything about Cortázar as I find his writing a bit tedious and predictable. If I’d been alive when it first came out, I may have liked it.

If I read it enough times, I may start to like it.

If I make the effort to connect the work to the historical context of the time it was written, I may appreciate it on that level.

But isn’t it still tedious?

Surrealism requires-

I think surrealism needs to have-

+

Someone who appears on this site a lot and whose name begins with Danik told me that it’s good to write about something you struggle with, or outright despise, and now that I think about it, she didn’t tell me that, she was just agreeing with what I’d said to her in the previous e-mail. But we’re both right. I think there is something to be discovered in this work.

And I do actually like surrealism. Absurdism too.

Because it helps me to hide from something?

+

In my meandering-sci-fi thing, Planet Rasputin, I used absurdism as a lever to help me get to a 2114 that would allow anarcho-communism in Slovenia and Ghana and several other nations in the world. Then I put all the characters on a space-ship and used absurdism again to cover up my weak grasp of science.

That was hard work, but absurdism made it much lighter.

+

In Cronopios and Famas, Cortázar uses surrealism to…do what?

Satirize the politics of Argentina, Peron and the military dictatorships of the 60’s?

Was he even there at that time?

+

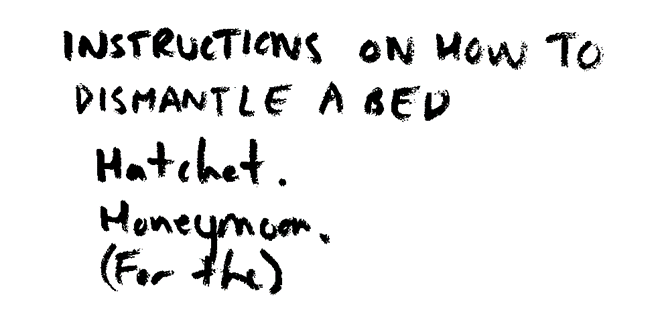

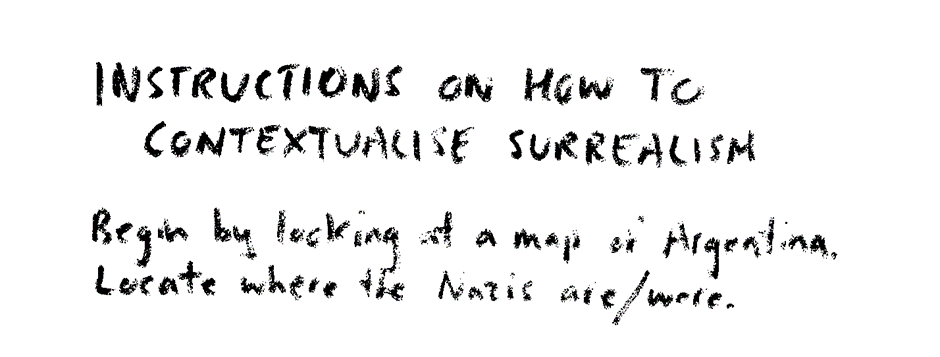

The first section of the book is called the Instruction Manual and contains a series of absurd instructions like:

Instructions On How To Cry

Instructions On How To Sing

Instructions On How To Understand Three Famous Paintings

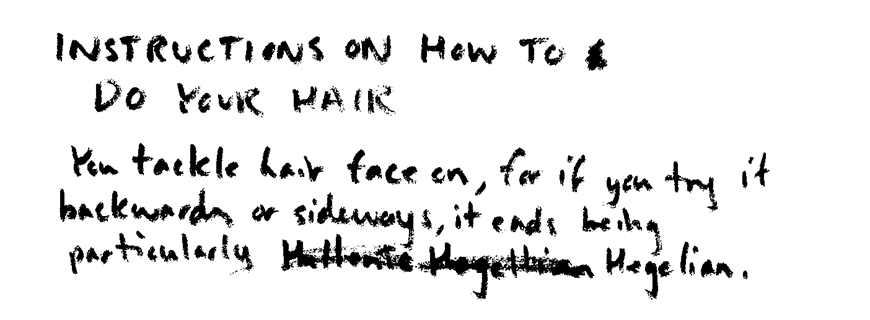

Instructions On How To Comb The Hair

Instructions On How To Dissect A Ground Owl

Instructions On How To Climb A Staircase

Etc.

The point of all this is obviously to-

+

The point of giving instructions to the reader is to make sure they understand that the way they were combing their hair and climbing staircases previously was incorrect, but it’s okay, Big C is here now, and if you learn his way of doing things in every sphere of culture and life, or the few he has selected for this book, then there is no longer any need to vote.

Or think.

Peron invested heavily in social welfare programs and built up the strength of the trade unions.

Peron allowed Nazi war criminals to live in the countryside.

Peron introduced women’s suffrage.

Peron controlled the press.

Peron improved working conditions and wages.

Peron put his own puppets in the trade union leadership roles and tortured some of the previously elected ones.

Peron nationalised key industries.

Peron got rid of 2000 professors from the universities [that’s a big number, could include faculty members too, and all educational institutions, not just the universities]

Peron dated a teenager after his wife died.

Peron came back from the dead and tried to turn everyone into plant seeds.

Peron hated Surrealism, despised Breton.

Peron founded a sci-fi magazine that said it wanted experimental work, not the same old, same old, yet when Cortázar submitted an early version of Hopscotch to that magazine, he got a form rejection within two days, which made him think Peron hadn’t even read his story, probably fobbed it off on one of the interns or-

+

I’m not sure what Cortázar’s politics were, but I like to think he didn’t like at all what happened in Chile in 1973.

I’ve thought about it a bit more and I now believe that the point of the instruction manual section was to scratch an itch.

Why a staircase, or a ground owl?

Doesn’t matter.

Just the idea of writing out something that doesn’t fit, that will perplex people, that sounds ludicrous when you read it back to yourself, yet it does have something within it, doesn’t it?

Why should he have to make sense with his words when the politics of the world doesn’t offer the same concession?

Sorry, Peron, but this is how you need to comb your hair.

Am I on the right track?

The next part of the book is a collection of nonsense that is almost grounded in reality but not quite. Take the first paragraph of the first story, Simulacra:

‘We are an uncommon family. In this country where things are done only to boast of them or from a sense of obligation, we like independent occupations, jobs that exist just because, simulacra which are completely useless.’

He then goes on to tell of the family building a scaffold that they promise won’t be used to hang anyone. And I don’t think it is. They end up having dinner on it, with the rope swinging above in the breeze, after the cops have come to compliment them on the fruits of their construction.

‘…it was not difficult for her to persuade him that we were labouring within the precincts of our own property upon a project only the use of which could vest it with illegal character, and that the complaints of the neighbourhood were the products of animosity and the result of envy.’

Is this magical realism, the genre that South Americans pretend they’ve had enough of but keep churning out?

There is a realistic setting, and realistic characters, with the only odd thing the gallows they are constructing, for the reason of doing something completely useless.

The meaning of this imagery – a scaffold – seems obvious enough, and universal, but what about the Argentinian context? Does the building of the thing on private property, endorsed by the cops, under the insistence that it is just for show, have some extra relevance to Argentinian culture of the 50’s/60’s that I don’t know about?

I don’t want to look stupid.

There may have been a literal case of a family building a scaffold in their garden in order to intimidate their neighbours.

Doesn’t seem likely though.

If there were, why would Cortázar write about it so literally?

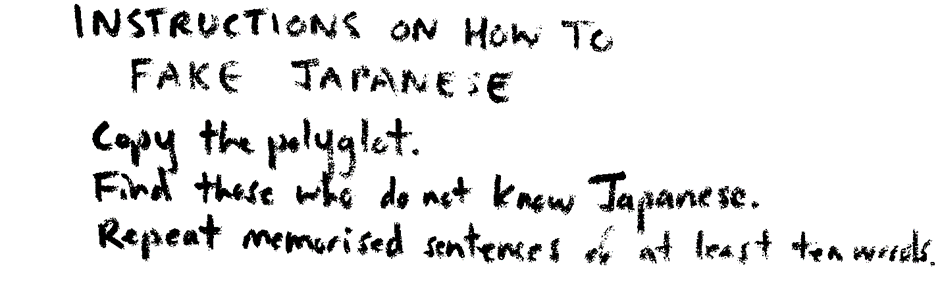

I cheated and looked up Cortázar on wiki.

It had to be done, I just don’t know enough about him and maybe I should’ve just made it up?

Don’t know.

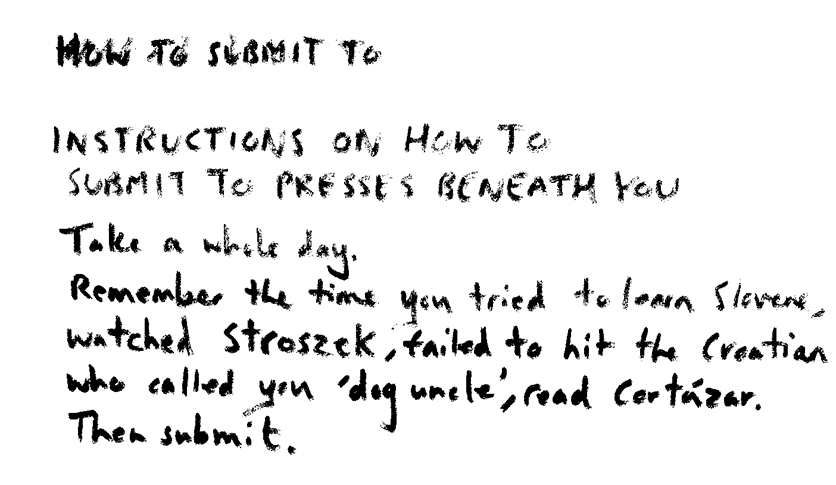

But according to wiki, he supported the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, Allende in Chile [I knew it!] and Castro in Cuba. Not sure what he thought of Peron, just that he left Argentina for France in 1950 and never returned.

I guess they weren’t close.

The question is: is any of this work dealing with that?

Does Surrealism ever address real events except as a way to avoid them? Or deal with them abstractly and hope someone figures it out, but not enough for them to get a visit from an overseas assassination squad?

I mean, Cronopios and Famas could be about Peron, could be about De Gaulle, could be about general sociological ennui, could be about the military dictatorships that followed Peron, could be about Cortázar’s absentee dad, could be about something that even Cortázar himself wasn’t aware of.

Or something that he sensed, that he could access at times, but five years later, when he went back to read what he had written, thought, huh, what is this?

+

Are we in this to communicate?

+

Cortázar was a sickly child and spent most of his formative years in bed with his mother, reading books.

Just like Proust and another writer I’m blanking on right now…

Lovecraft?

I’m sure there are plenty more too, writers that developed a sense of insulation in their childhood and kept it well-irrigated as they got older. I’ve done the same to a degree, though I wasn’t the sick one. I won’t elaborate on that. I’ll just say that I lived inside my own head a lot, and books, and I still do and that’s why most of my writing is so disorganised. And when I’m tasked with writing something formal, I struggle badly, until I find a way to make the whole thing collapse in on itself. That or just try to go back to writing my own way.

This insulation…could be the root of all his writing…an attempt to climb up to the same pedestal as Borges or Breton or other surrealists who were a generation older than him.

Never has my speculation been wilder.

I have absolutely no idea about anything Cortázar-related.

But I could be right about this.

Eventually we reach a new batch of nonsense, the eponymous Cronopios and Famas section.

I don’t mean nonsense in a negative way.

I like nonsense.

As long as the word choice is good and there’s some flicker of madness in there, and it doesn’t come across as some drawn-out sketch of pedantic cleverness like the Instruction Manual did.

Not that I hated it.

I didn’t really feel much of anything.

Just a sense of yes, I understand what is coming next.

The opposite of Maldoror.

+

How does this read?

‘It happened that a fama was dancing respite and dancing Catalan in front of a shop filled with Cronopios and esperanzas. The esperanzas were the most irritated. They are always trying to see to it that the famas dance hopeful, not respite or Catalan, since hopeful-…’

On some level, I like it, the randomness, the pedantic nature of the esperanzas, the irony of them insisting like dictators on a dance of hope.

Esperanza means hope, right?

I may have to check that, I’m not sure.

But on another level, I couldn’t really give a fuck.

What’s the word? Twee?

That’s what it reads like to me. I’m sure C is saying something here, something satirical or pointed, but I do not believe any of these famas or Cronopios or hope creatures reside in the same reality as myself. I do not believe in their existence even in a surrealistic realm. Does that make sense?

I’m really struggling to continue with this. Feels a bit insulting to Cortázar even though he’s long dead, but if something feels predictable, shouldn’t I stop?

If I just focus more, try to figure out what these cronopios and famas are representative of…what the point of it all is…

I don’t usually care about points.

Yet I do.

I want to know what this means. I want to be able to understand it myself without looking up some review or analysis that tells me exactly what it’s all about. When I was in high school, I had to constantly be told what was really going on in King Lear. And each time I got told, I thought, ah, I guess that’s obvious enough, why didn’t I pick up on it?

Later, in the exams, I argued that the fool was actually a ghost and got marked down for it. But he was a fucking ghost. I’m sure of it.

How was he not a ghost?

He never eats, looks kind of grey, doesn’t seem to care much about the storm, vanishes near the end just before Lear dies.

Does he die?

Can’t remember now. I’ll have to look that up too.

But I remember feeling quite happy with myself at the time, cos I’d come up with my own [pointless] interpretation of the text. And now I’m writing de-con-struc pieces about works I have marginal contextual knowledge of.

If Cortázar read this shit, he’d probably spit his liver out.

+

I’ve decided to continue.

Wiki tells me that Bolaño adored Cortázar and was heavily influenced by him [and Borges] so I should give it a try.

Also, I stuck with Rebecca Gransden’s Sea Of Glass [after the first page, where the description almost killed me] and that turned out to be pretty good. And Jace Brittain’s Sorcererer when I didn’t have any clue what was happening in the first ten pages.

Sometimes you’ve got to push yourself and, after it’s done, little parts will stay lodged in your brain, like a happy splinter, or a dinner table scaffold, and you’ll try to work your way through what it might mean.

That also happened with Spirit of The Beehive, which I fell asleep watching the first time.

Never happened with Tarkovsky though.

Not sure why.

His films are deathly slow yet I didn’t care, I felt comfortable throughout, and was not stressed in the slightest about what any of it might mean.

+

Cronopios & Famas [& Esperanzas sometimes]

I checked the Spanish and Fama means fame or reputation, Esperanza means hope, and Cronopio means cronopios.

Here’s the intro to these wispy representatives:

‘It happened that a fama was dancing respite and dancing Catalan in front of a shop filled with cronopios and esperanzas. The esperanzas were the most irritated. They are always trying to see to it that the famas dance hopeful, not respite or Catalan, since hopeful is the dance the cronopios and esperanzas know best.’

So the famas are the good guys? The rebels?

Esperanzas offer tyrannical hope, or the symbolism of it?

Cronopios, in the rest of the section, go on to do little except watch and act unsure about how to respond to anything.

Yet:

‘A fama is very rich and has a maid. When this fama finishes using a handkerchief, he throws it in the wastepaper basket. He uses another and throws it in the basket. He goes on throwing all the used handkerchiefs into the basket. When he’s out of them, he buys another box.’

The first section is turned on its head, or my head, as the famas are rich enough to dance how they want in public without worrying about consequences.

They are the elite? The liberals?

But then:

Where does the policeman fit in?

The cronopios do not know him beyond the uniform, but in this kind of public situation is that relevant? He is both the uniform and whatever failings put him in there, plus whatever degree of power is invested in said uniform by the state, which can be a] a lot, b] more than a lot, or c] an unassailable totality.

+

The famas are a multiplicity of things/acts:

They get away with flagrant public behaviour, like dancing respite and Catalan.

They’re in charge of the factories.

They are meticulous when they travel.

They are more philanthropic than cronopios [which punctures the dialectical materialist angle a little as most studies show that the poor/working class give a greater percentage of their wealth to charity than the motherfuckers at the top.

Was Cortázar part of the elite?

His wiki page said he was supportive of leftist movements across South America and in Cuba, I think I said that already somewhere above, but he definitely wasn’t working class. Which means:

A] he doesn’t know what he’s talking about when it comes to the cronopios

B] the cronopios are not representative of the working class

C] the cronopios are representative of the working class but he was trying not to patronise or deify them.

D] both the famas and cronopios occupy a grey zone [not the tankie site run by nepo kids] where their positions shift and diverge in unison with the Peronists.

Is this related to Argentina?

Is it beyond me?

Yes, and so is most surrealist work, that’s the point. What Cortázar got out of his work and what I get is the difference of affection – he gives his words time, remembers them, I go in cold, with zero history – and also how many times he forced himself to edit the thing.

Read ‘it happens that cronopios do not want to have sons’ enough times and it can drive you to hatred. And a lot of these lines are whimsical, from a different era where authors still respected a kind of linguistic formality…perhaps a class distinction…and the word choice can’t glow quite the same way cos those words aren’t used as much anymore. Whimsical and dated. The same way what I’m writing now will be whimsical and dated in 2073. You can tolerate it for a while, but how long after that?

+

Don’t want to give the impression there are no good lines here. There are. Look:

‘A fama is walking through a forest, and although he needs no wood he gazes greedily at the trees. The trees are terribly afraid because they are acquainted with the customs of the famas and anticipate the worst.’

But they could be sharper.

And less whimsical.

What is it exactly that an exile wants to say about Argentina?

The answer must be buried deep in the text, beyond sub, maybe even beyond quantum too. But only to someone like me who knows very little about Argentina in the 1950/60’s. To his compatriots at that time, the whimsy is clever, the abstractness refined.

I would like access to this state of being understanding.

But I don’t want to put in the hours. Or cheat by reading a What Does This Book Mean book. The writing as it is does not motivate me enough to do so.

It’s really true that you can like the idea of someone, an artist, but feel a sense of blankness when you read their work.

Surrealism always carries that risk.

+

If I’m not gonna understand the text…

‘Now it happens that turtles are great speed enthusiasts, which is natural.

The esperanzas know that and don’t bother about it.

The famas know it, and make fun of it.

The cronopios know it, and each time they meet a turtle, they haul out the box of colored chalks, and on the rounded blackboard of the turtle’s shell they draw a swallow.’

…then turtles.

I’m assuming the swallow is Lenin.

Or, in the South American context, Bolivar.

Peron?

+

Cronopios and Famas is available at my local library, and probably yours too.

+