+++

Text: A Hero Of Our Time

Author: Mikhail Lermontov

Publisher: Blank Bela Press

Plot: A beautiful, nihilistic magnet, Pechorin, alienates himself from false notes and safe melodies and convinces other 19th Century Russians that he’s a wonderful fellow, albeit a bit strange.

Subplot: Several women try to fall in love with a man who may be a sociopath but it’s a sociopathy close to something liberatory and will do until October comes around.

Sub-sub plot: A depressed lump of nothingness wanders around London in 2010, dumping zines in places that don’t want them, chasing an unresponsive female Pechorin, writing notes on Lermontov, fighting off a mutated type of pessimism.

Note: Around 60% of this was written back in 2010 when I was a very different [worse?] person. Somehow I survived and am still here.

+++

[‘Shoot!’ he answered. ‘I despise myself, and I hate you. If you don’t kill me, I will stab you from around a corner one night. There isn’t room on this earth for both of us…’]

–

It’s grey outside, the leaves are folded over, and those drunks in the sex pest park opposite won’t stop calling each other ‘brother.’

I don’t want to go out there.

I won’t.

I’m going to write about Lermontov.

A Hero of our time, the first Russian novel, says the guy writing the forward foreword. The first psychological novel too, perhaps. I’ve read it all the way through, not sure where to begin.

It’s about a sociopath, but a man who’s aware he’s a sociopath, is unafraid to tell everyone.

Edit: unafraid to tell those who get too close. Others have to divine it from his behaviour/casual recklessness.

–

The introduction…is descriptive, a whole paragraph of Chechnya or the Caucasus [?] mountains and some guy riding through it. Is he the main character?

–

Nature does nothing for me. No book should start like this. People make things come alive, not mountains or plants.

Scenery’s fine for metaphor, but it’s not sentient, doesn’t do anything except what it always does. There’s no second note, no emotion.

–

PKD never wrote about scenery.

–

What else?

+++

The water ran cold before the bath was deep enough.

I went to the kitchen and put the kettle on then walked back to the bath and stared at the surface of the water.

The phone rang again.

Jay, not Kaia.

I ignored it, went back to the kettle and poured the boiling water into the tub.

Submerged, I put a hand palm-down over the surface and tried to raise the water. I tried it a few times, but it would not move.

What more do I want? Immortality? For what?

After washing myself/sweating from the heat, I sat on the floor with towel over head and phone in hand.

–

‘Any human with superpowers leads to amorality, leads to a more miserable version of myself, this.

But if offered powers, could any human say no?’

–

Any ‘yes’, even for a short time, still leads to MMVofMyself.

Can’t give up something that lets you control others, it’s impossible.

Murder might take a while. It’s hard to kill, normal people would still look and sound like you.

What about sex, a more obstinate Bela?

Would I?

+++

+++

[‘His name was…Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin. A wonderful fellow, I dare say. Only a little strange too.’]

–

Pechorin is not present?

It is a telling of a tale about him, told by friend and fellow soldier, Maxim Maximych.

A close friend?

Sociopathic soldier?

+++

The next day the zines arrived.

The delivery guy, a bloated David Warner, carried six boxes into the living room and dumped them without care in the corner. I didn’t mind, zines wouldn’t break and the corner wasn’t really used for anything. Neither was the flat, really. I didn’t have many possessions and all the things I did have could fit easily in my room. In fact, if you looked at it from the doorway, the living room didn’t look much different than one of those nuclear test site homes.

Like in that mutant hill with eyes film.

Or Indiana Jones.

Only without the dummies.

What would it be like to be frozen in the body of a dummy, I wondered, and know that you were, at some point, going to get nuked?

Someone started a car outside and snapped me out of dummy thoughts.

Jesus, what am I doing here?

I stared at the living room as if it were a super-sized cardboard dollhouse holding a note of paper that said, ‘Kaia’s an accountant now’, then went to the kitchen and got some scissors. I walked over to one of the boxes, cut the tape, and picked up a zine. Was it any good? The cover didn’t look too bad, not art exactly, but it was different.

I flicked along a few pages and, as usual, smiled at my own work. The stuff I’d written before I came here, in the times when I was good.

There were some decent lines and I flicked a nail at them [scratched it down their cheek]. There was gamble too. I admired himself for taking it. The spirit of times past. Filming in the slop alleyway, Kaia talking different shots, real things happening.

This time, this time they’ll-

Dried out, colourless, I put the zine back on top of the box and went to get the rucksack. A hundred at a time, they’d be done and gone in a week.

+++

+++

[‘’Listen, my peri,’ he was saying, ‘you know that sooner or later you will have to be mine, why do you torture me so? Is it that you love some Chechen? If that is so, then I’ll send you home now.’ She shuddered just noticeably and shook her head. ‘Or,’ he continued, ‘am I completely hateful to you?’]

–

He is charming a kidnap victim, but is this charm?

The novelty of the sociopath is irresistible.

The sociopath will think this.

On some level, he knows it is pathetic what he does. Not a challenge but merely a process by which a young girl will become accustomed to him as there is no one else to mark a challenge.

I would not bother with this.

I have done it already.

And what for?

+++

There was a list of places I’d taken from online.

Lik + neon

56a

The Alibi

Bermondsey Hyperstore

Rough Trade East

…and a whole load of others I really didn’t want to go to.

But, still, I got on the train and headed up to Hackney and Dalston and Old Street, and went into all those places and asked them if I could leave my zine.

‘Who’s doing it?’

‘Me.’

‘What’s it for?’

‘Nothing.’

‘How you gonna make money from it?’

‘I’m not.’

They were the usual questions, and I no longer tried to make the answers interesting. Why bother? I’m not selling it, it’s free.

+++

+++

[‘I have an unfortunate character – whether it is how I was brought up, or whether God created me this way, I don’t know. I only know that if I am the cause of unhappiness in others, then I am no less unhappy myself. In my early youth, from the moment I left the care of my parents, I began furiously enjoying all the many pleasures you can obtain for money, and then, it seems, these pleasures became loathsome to me. Then I set forth into the wide world, and soon I’d had enough of society too.’]

–

Byronic hero contradiction, according to Byron.

Could also be described as mood.

Is there a single person on this planet who doesn’t stare at the ceiling with dark thoughts after watching Jurassic Park 3 or some other sludge? Searching for ‘Kitty Zhang sex tape’, is there not a simultaneous shot of disgust?

This is not contradiction.

I don’t see it that way.

+++

It was a few weeks since I’d last seen Kaia.

She’d been offline, off radar, off everything that had roots in the outside world. Was she dead? Haunted by the ghost of Grushnitsky?

No.

There would’ve been-…someone would’ve known.

She was hiding, obviously.

What did she do when she was hiding?

I sat in my coffin room, with grey sky hovering outside the window, and thought about calling her.

‘Kaia?’

‘Oli.’

‘Are you okay?’

‘It’s too early. I can’t talk.’

‘It’s afternoon.’

‘I just got up.’

‘You don’t wanna talk?’

‘My head isn’t working right yet. It’s too early.’

‘It’s been a while.’

‘I’m no different than I was the last time.’

‘Are you okay though?’

‘I need space.’

‘You want me to-‘

‘Please, I can’t listen to questions right now.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Question, question, it’s like a script.’

‘I better go then.’

‘Even better questions, doesn’t matter, same thing.’

‘I know…’

‘Why do we bother with any of this shit?’

But I didn’t call.

And she wouldn’t have picked up anyway.

+++

+++

[‘I wanted to comfort him, and started to say something, mostly out of a sense of decency, you know. And he raised his head and burst out laughing…a chill ran along my skin with that laughter…I went off to order the coffin.’]

–

Bela is dead.

The narration is not from Pechorin but his half friend Maxim, who is going off of memory. It is implied that there is feeling here, and sociopathy. Did he love her? What for? She would’ve left him eventually, he would’ve left her. A predator cannot love. A Byronic predator can laugh at the meaninglessness of it all. The grave is coming. Prepare or don’t.

–

I’ve just realised that the next part is from Pechorin’s own diaries, which will bring us closer to how he thinks.

I sense that he won’t explain anything, that he won’t know how to.

–

Does he ever think that others might think the same way?

That he bores Vera to some degree?

+++

I, Anaemic Pechorin Simulacrum, took the train over to Camden, a hundred zines on my back.

‘What’s it for?’

‘Nothing.’

‘You make money from this?’

‘No.’

‘Nothing, zero?’

‘I throw it into the sea.’

‘Huh?’

+

There was a canal splitting Camden in two, one side clean, the other a slum. I found a place to cross and walked over to a bar on the slum side, clutching my beloved zines.

‘What’s it about?’ asked the woman inside, who looked a little like a bookish version of Princess Mary, the actress who played her in the Soviet film.

‘I don’t know.’

‘Haha, this is your mag, isn’t it?’

‘It’s hard to explain.’

‘Hmm.’

I pointed at the zine spine. ‘It’s got Nick Stahl in it.’

‘Stahl who?’

‘The movie star. He was in Terminator: Autophagy, and that other thing…the film with the big wave.’

‘Xeno-Ship?’

‘Not that one.’

‘Big wave…’

‘That was in space. I’m talking about the-…’

‘…ocean. Ah, okay, I thought you were talking about a space ship and solar waves or whatever.’

‘No.’

‘But I get it now. Water waves. Still don’t know who Nick Stahl is though. Or what this green thing is. Slime monster? Alien?’

The Mary clone flicked through the zine and continued to not know a thing, but took twenty copies anyway cos there was fuck all else in the bar.

Like most things in London, it looked like a warehouse.

As I exited, three teens walked by and called me a ‘fucking tramp.’ Not a ‘Byronic tramp’, just a ‘fucking’ one. I called out ‘what?’, stopped and waited to see if they would stop too. They didn’t. They kept walking, eventually jumping up on the railings and spitting down on a canal stuck in the lock.

Camden never used to be like this, I thought.

+++

+++

[‘I learned not long ago that Pechorin had died upon returning from Persia.’]

–

Dead halfway through the book.

Like Maurice Ronet in Purple Noon.

The order of events is non-chronological, it said this in the introduction [that I shouldn’t have read], so I’m not surprised.

It’s no big deal to be dead if you were bored of living.

Am I bored?

Is there a limit for that, to measure it?

I just read that Lermontov died in his twenties, fighting a duel. Early 19th Century Russia was like that, I suppose.

Did his death encourage others to die young too?

To bow out cos why not?

+++

I stretched out in the bath which wasn’t as hot as I wanted it to be and thought of three things.

How to raise water with my left hand [of darkness].

The three teens who weren’t bold/angry enough to spit at me.

Kaia the Pechorin clone.

And then another.

1820’s Caucasus.

+++

+++

No idea what ‘Taman’ is about.

Name reminds me of a guy who used to annoy me at footy.

Skip.

+++

The zines and the boxes were almost gone.

Maybe fifty, sixty left.

Dead as a rock spiritually, I looked online for places to put them, but it was too hard to search for anything. There was no root word that would lead me anywhere. ‘Zines in London’ was useless. ‘Shops with zines’ even worse.

I walked over to the last remaining box and kicked it.

What’s the point, really?

I kicked it again then walked back to the computer and with a fair amount of bile typed ‘literary events London’.

The results appeared.

Some pub near Clerkenwell. Wolverine had read there a few months earlier, milk leaking out his mouth.

I stared at the screen.

Wolverine the Fraud. Wolverine the milk sexer. Wolverine the light pillar of dust curled up at the edge of the precipice. Wolverine the Ba-

The phone rang.

Jay.

Of course, Jay.

Jay the Fraud. Jay the-

‘Haven’t been anywhere,’ I explained, eyes fixed to an old blood stain on the living room wall [Prince Taob ritual?].

‘You’ve gone dark, bats.’

‘Just staying home. Delivering zines.’

‘Do what?’

‘Delivering zines.’

‘That’s it?’

‘Yup.’

‘You got a job yet?’

‘No.’

‘Nothing?’

‘I got savings, from the last thing.’

‘That’s your priority, bats. Nah, not savings, forget that. Remember what I said, no job and you’re just bleeding cash. Get a job, you can start thinking about all that other shit. The writing, magazine thing, whatever.’

‘I’ve gotta go.’

‘Go where?’

‘I mean, I can’t talk right now.’

‘Ols…’

‘Bye.’

‘You can’t keep-‘

+++

[‘Stare into Uranus. Jump.’]

–

I will not.

+++

I, Pechorin the Bored and Pointlessly Internal, strolled into the book + baby-milk powder store near the building site next to the station I couldn’t remember the name of and picked up something by that milk sexer Wolverine.

It started badly, had a loose plot, characters that operated with okay charm and zero madness.

Relieved, I put it back.

Was it that bad?

Too American?

So good I can’t allow myself to see it?

Gormless confessional?

Superfluous man?

Confused, I picked it back up and read a little more. Something about a man waking up and stretching his legs and being surprised that it was so easy to stretch his legs, and wasn’t it great to be alive and-…what was this? Foreshadowing?

I shook my head, mentally, and put the trash back on the shelf. Worse, I turned it the other way round so the edges of the pages were facing out.

Foreshadowing.

I knew what it was.

It’s Danny Glover telling everyone he’s about to retire.

It’s Pechorin getting ready to fuck Bela before the Devil does.

It’s Kris Kelvin walking around a pond in Russia, forgetting and remembering and forgetting and ultimately incinerating his wife, staying with her for eternity.

But Wolverine…

A breeze from Oymyakon sailed in through a nearby open window, forcing me back to the last batch of zines, the pub near Clerkenwell. I’d gone there and left fifty of them, next to the scuzzy umbrella rack…for what?

My eyes fell back on the shelf.

Or they were already there.

The book next to the Wolverine shit I’d picked up was another copy of the same Wolverine shit.

And the one next to that was Wolverine too.

And the one next to that-

I walked out of the book + baby-milk powder store, sick of every fucking word in there.

+++

+++

[‘He will never slay a person with one word.’]

–

There’s no point writing anything, focus on real world stuff.

Think like Jimmy Stewart. Pure sangui-…optimism.

–

Prisoner exchange – look up prisons in UK or US, find anyone who’s not looking for a fuck.

They won’t write to me.

They’re psychopaths.

I’m not that interesting.

They’re all looking for a fuck.

Try anyway.

–

Go to the youth centre near Kwik Save, see if any kids would be interested in doing zines or writing anything.

Don’t pretend to be one of them, just be myself.

–

Go to 56a zine store, see if there’s any troubled kids hanging around?

Should I?

Some might be decent, but it only takes one to stab me.

–

Story idea:

Near future, a guy teaches troubled kids private lessons, and at the same time has treatment for his own previous-…for beating people before.

His treatment is done in a special clinic, it’s like Star Trek, they can recreate previous events on a holodeck.

Aim: to make the character better he has to relive beatings he did before on the holodeck.

The kids he teaches are all cunts too. Better this way as all troubled kids are cunts until you help them, that’s why they’re troubled.

Don’t romanticise any of it.

Title: Psycho Holosuite?

+++

+++

[‘There is female company but they don’t provide much consolation: they play whist, dress badly, and speak terrible French.’]

–

French was the language of Russian elites of that era, if you didn’t speak it, you were the equivalent of a Roddy Doyle character.

I remember this from The Devils, Dostoyevsky’s childish Orthodox panic at the future revolution, the spirit of Anarchism.

Where is this in Pechorin’s life? Pre- or post- Bela?

Does it matter?

He didn’t love her.

I feel sure about that now.

+++

Xerography Debt was inviting people with zines to send their zines to them so they could put it in their zine and I’d never really heard of it before, Xerography Debt, but then I’d never really heard of anything outside of 56a and Housman’s and that place I went to in Hong Kong so I got an envelope, filled out their form and sent my zine and then went back to their website and looked at a promo for an upcoming event in Baltimore that I wouldn’t have to worry about going to even though I would like to go if I could, if I were in the same city and the people didn’t terrify me with their bland wants, their unwillingness to put a pistol to their head and-

Maybe I should see if 56a was organising anything?

It wouldn’t be so bad if they were, only a few people, other souls who made zines and didn’t go out much.

The phone rang.

It was Jay.

Always fucking Jay.

+++

+++

[‘I couldn’t help remembering one Muscovite lady, who had assured me that Byron had been nothing more than a drunk.’]

–

This precedes the death of Bela, Maxim relaying the words of Pechorin and how bored he was becoming of her, and whether or not that had infected the Russian youth at large.

In short, were they in a Gregg Araki film?

Drink is to blame?

I’m wondering, about Pechorin, his sociopathy, the way he listens to Bela as she lays dying without saying a word. Is this affecting him more than what happened with Vera?

This is after that event, but before it in the book.

Why?

Is this important to me, the Vera thing, the precise quality of their love?

I feel like I’ve written about it already.

He clearly doesn’t care enough about either of them. There is no heart that can be forced to yearn for something.

His heart knows this, feels guilt.

Alone is always better.

+++

The bouncer wouldn’t let me in with the bag.

I didn’t want to go in anyway.

It was Friday night, there was no space inside, and it was some part of London I didn’t know or care about. Jay wanted to come here, not me.

‘I told you, not with the luggage, mate.’

‘There’s nothing in it.’

‘No.’

‘Just some zines, or books, random stuff.’

‘Not with the bag.’

‘It’s-…’

‘No.’

‘I’m not doing anything with it.’

‘Go.’

‘But it’s-…’

‘Now.’

‘Jesus fucking-‘

‘I won’t be telling you again.’

‘Okay, relax, I’m going. See, I’m going.’

I tried to go, but there were too many people to get past.

‘Could you-…’

A few seconds later, the bouncer put a hand on my shoulder.

‘Move to the side, mate.’

‘I’m trying.’

‘You’re in the way.’

‘It’s these guys, they’re-…’

‘Move.’

‘I’m trying, fuck’s sake.’

+

Jay said it didn’t really matter, the place was just too packed. It wasn’t an indictment of London or anything.

I didn’t care.

‘Why do you always go out on Friday?’

‘You serious?’

‘It’s worse than Shibuya.’

‘People to talk to, bats. Uni students who don’t have anything going on tomorrow.’

‘Too crowded. I don’t like it.’

‘High school students who don’t have anything going on-…joking. Don’t give me that Sean Penn face. I’m joking.’

‘Should’ve stayed at home.’

‘High school students are off limits. The obvious ones. Fucking hell, you’re tense.’

+

We tried to get into a bar with its entrance under one of the tunnels – the one Peter Coyote got stabbed outside of a few years back – but there was no sign anywhere so it was unclear what the place was called. Didn’t matter much anyway, the bouncers didn’t like the way either of us were dressed.

Jay said one line, how he’d just come from court and the suit was a good one, but it fell on stony ground.

+

No choice after that but to walk down the street and buy a couple of beers from one of the shops and then stand on the pavement, talking about all the other, more exotic things we’d done before.

‘You gotta cut the negatives, bats.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You’re feeling sorry for yourself. It’s not a good face to have, not if you wanna…’

‘I don’t have that face.’

‘…meet people or-…serious? You’ve got it right now. Sean Penn face.’

‘I feel good.’

‘No, you don’t.’

‘I do, really. Things seem okay, I’m not down about anything. I’m just lying low, waiting for-…’

‘You’ve been gone for weeks.’

‘Weeks?’

‘You’re burying yourself, bats. I did it when I came back too.’

‘I’m not burying.’

‘And that’s why I can tell you this, cos I know what’s happening in your head, and I know how to beat it.’

‘I’m okay, really.’

‘You’re at half speed, that’s what it is. And it stays with you for two, three months, whatever, but once you’re past it, things get bright again.’

‘Jay…’

‘And you don’t even have to do the three months. You can fast track it, because I’m your mentor, or spirit guide, whatever you call it.’

‘Are you listening? I’m fine.’

‘You’ve just gotta force yourself out, go to events, meet people, then it won’t get a grip. Yeah, I’m listening, course I am. I’m pulling you out of this fucking thing.’

+

We drank up the beers and bought some more and talked about other things and, a couple of hours later, we were in another bar, a more casual place where everyone looked a weird shade of green, possibly cos of the lighting.

Propped up near the corner, we talked over what sounded like post-feudal rock.

‘What?’

‘Gotta write that script, bats.’

‘Script?’

‘You write it, I edit.’

‘Me write it?’

‘What?’

‘You want me to-‘

‘What?’

‘I write the script?’

‘You write, I edit. Then we take it to Hollywood, bats.’

‘What?’

‘Hollywood.’

‘Go to Hollywood?’

‘What?’

‘I hate Hollywood.’

‘Yeah, go to Hollywood and sell it. But the only thing is, how to stand out from the dregs, brother?’

‘Man, I can’t-…’

‘What?’

‘I can barely hear a word you’re saying.’

‘What?’

+

Walking back home at three in the morning, drunk enough, I rambled into my problem with London, the constant dreaming of 1820’s Chechnya, the bizarre positivity I had for everything I was on the verge of doing, but mainly my problem with London. Meanwhile, Jay fucked about with his phone.

‘I know everything here already…’

‘Yeah.’

‘…the way the buildings look, the trees, the shitty grey pavements, the roads…’

‘Rainbow road.’

‘…the parts where it’s under construction, the other parts where they say it’s under construction but no one’s there, no one’s doing anything.’

‘Any Which Way But Lose.’

‘I mean, what’s so good about this place anyway?’

‘As good as it gets.’

‘If you’re not from here, then yeah, maybe it’s okay, maybe all these things are new and exciting and-…all those Ozzies and North Koreans and Polish guys in the hostels…’

‘Ozzie Ardiles.’

‘But it’s not the same for us. It’s…I don’t know. What is it?’

‘What’s that?’

‘Maybe I’m being too harsh.’

‘Harsh? You whine like a mule, brother.’

+

By the time we got to Paddington we’d fallen into an old default.

‘Jason Lee. Kurt Russell. Go.’

‘Jason Lee…’

‘Yup.’

‘…and Kurt Russell.’

‘Yup.’

‘And it’s a movie?’

‘Yup.’

‘A real movie?’

‘What do you mean real movie?’

‘It’s not animation?’

‘Nope. Real live faces.’

‘And it’s got Kurt Russell in it?’

‘Yup.’

‘And…Jason Lee?’

‘Yup.’

‘Soldier?’

‘What?’

‘Nothing. I was just-…never mind.’

‘Never heard of it.’

‘It’s-…forget it.’

‘Is Jason Lee in it?’

‘No, not really. Well, kinda. It was Jason Scott Lee. A different guy.’

‘That’s not him.’

‘I know.’

‘Do you know who Jason Lee is, bats?’

‘Yeah.’

‘You sure? Cos it’s okay not to know something. I won’t shame you or brag about it or…’

‘Fuck off. He was in Mallrats.’

‘Mallrats?’

‘He was.’

‘Maybe.’

‘Mallrats and…’

‘And?’

‘The thing with the…’

‘The what?’

‘Give us a sec, it’s in my head, I just can’t-…’

‘You won’t get it.’

‘Shut up.’

‘You’re not even close.’

‘I am. I got it, I just-…’

‘Face it, bats, you just don’t know film like you thought you did.’

+

On the train Jay told me again, for the four hundredth and twentieth time, about the importance of getting a job. Apparently, it was non-negotiable, and the sooner I stopped fucking around feeling sorry for myself and got out there, the sooner I’d have a more positive outlook on things.

I tried to say I had some cash saved from the last place, but Jay shook his head, said it wouldn’t last long and kept talking.

+

‘No job, no cash, no happy face,’ he concluded fifteen minutes later, folding his arms.

‘You’re done?’

‘Talking, yeah. But don’t say that, bats, it makes me think you weren’t listening.’

‘I wasn’t.’

‘Cos I can start up again if-…what? You weren’t even-‘

‘Joking, I got it.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Yup.’

‘Good. Cos it’s true, every word of it.’

+++

+++

[‘How many people begin life thinking that they will end it like Alexander the Great or Lord Byron, and yet remain a titular counsellor for the duration…’]

–

I don’t wish for either.

Pechorin is distinctive until he comes up against a more charming sociopath, a more callous nihilist, a male model with ripped abs.

He must know this.

It fits neatly into his nihilism, as in he could ride away and say it’s all futile anyway, who cares about a princess who likes someone else.

Like DiCaprio, all his conquests are young, naïve, initially stubborn.

There’s no female Pechorin to do to him what he does to others.

Does he want that?

Contradiction: he must conquer a woman, imbues the conquest with no real value.

He needs to meet himself.

Be constantly rejected, suffer from it.

And still be bored.

Sorry, Kaia, but I can tune you out too.

Fucking robot.

+++

The next day I walked around the apartment with a bag on my shoulder, trying to think of reasons to go outside.

On the living room wall was a poster. It wasn’t mine, it was there when I’d arrived.

Inspirational quotes, it said.

I read through them and tried to disagree. I knew they were motivational, that all these lines by clever people, all bunched together, should have had no other effect but total positivity. Yet still I disputed.

–

‘If everything could be said with words there’d be no reason to paint.’

–

That’s bullshit. Spoken by a painter, had to be.

I thought about philosophy and the programmes I’d seen on TV where smug people in turtle necks like Foucault would talk about art and power and systems and nihilism and explain what it meant.

Those were words.

How could paint reveal anything that words couldn’t?

It was ridiculous.

Tell me painters, tell me something that can’t be explained with words.

+

One hour later, I was on my way to 56a zine store in Brixton.

I’d been there before, but it was too brief – I’d looked at four or five zines then felt bored and anxious with the owner still in the room so I’d turned and left without leaving my contact info.

Obviously, I’d regretted that last bit on the train back, but I’d regretted a lot of things before and never corrected them. It just wasn’t my style.

My methodology.

Yet, for some reason, this time, today, I was doing it.

‘If you don’t get to know these people, you’ll just push yourself further and further and deeper into your rabbit hole and then where will you be?’

It hadn’t been in my head an hour earlier, but then suddenly it was. That’s why I was on the train to 56a.

It was weirdly persuasive, as if it was actually my own self talking to the person who’d been using my brain and body for the past 29 years.

That person was me, but not really.

Almost me.

An increasingly louder part of me.

A part of me that-…

Forget it.

It was too hard to classify.

+

Another thing that played in there, up there, among the Pechorin posters:

‘Got another 10 years then you’re dead. The world’s a shit place. Do something, fuck-head.’

It was angry and it was persistent.

And for some reason it was telling me to buy a lomokino.

+

Outside 56a, there was a long row of council houses and a shitty-looking park. There were no needles or graffiti or broken bottles, it actually looked quite clean, but I still knew what it was.

The place people come to get mugged.

The mug zone.

Death to people with no futures.

I did what most trespassers did in areas like this and put my hood up, stared at the three kids standing by the entrance rails.

Not that it would make much difference.

Everyone knew uni students [and ex-students] did the hood trick.

The key factor was: did I look like the kind of person who’d stab someone for looking at me funny?

Was there a scratch of Pechorin in me?

+

Eyes fixed on a theoretical centre of nothingness, I passed the kids and walked another ten metres to the info shop.

Apparently, according to their site, 56a was trying to help these kids. Give them skills like repairing bicycles and zine-making and watch them grow.

That’s what I want to do too, I told myself.

That’s why I’m here.

Do something, fuck-head.

That’s what I’m trying to do.

If I get the chance.

As long as they don’t stab me first.

+

I stayed inside the store for almost three hours, reading as many of the zines as I could, even the ones that looked like a waste of time.

The woman behind the desk was responsive, but limited.

I tried to ask her about other zine stores doing similar things, or if there were any local kids who were interested in zines, but she said no, most of the zines came from other cities, like Brighton, Nottingham, Bristol etc., and most of the local kids were too busy doing other things to come and visit the shop.

‘Busy? What are they doing?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Gangs?’

‘You mean, are they in gangs?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I don’t know. One or two. Maybe. You’ll have to ask them.’

‘Good idea.’

‘Not at night though, obviously.’

‘Right.’

‘And not with the hood up. Gives you an Oxford vibe.’

‘Hmm-mm.’

After that last line, I ignored her for the next hour, going back to zines I’d already read and dreaming about finding a kid who was on the verge of becoming a drug dealer but didn’t want to, and then the two of us forming a bond and making a zine together, and then going further, talking about politics, how unfair Brixton and the world were and, if we could solidify a workable brand of Anarchism, maybe form a party and stand for election, then we could take an area like Brixton and-

+

When I stepped back outside the shop, it was dark.

I checked my phone.

5 in the afternoon and it’s fucking dark already?

Only in London.

I thought about taking the long way around to the train station, avoiding the park where two of the kids were still hovering, but then I switched, telling myself it was the sign of a pessimist to avoid things, and if I judged these kids just because they looked like motherfuckers then I was already doomed.

They’re just kids, I repeated to myself, hood up, as I walked past them.

And they were.

They didn’t even look at me.

Weird.

Maybe I did look like the kind of guy who would stab someone around the corner one night.

Or maybe they were just too bored.

To shout, stab, do anything.

+++

+++

[‘Grushnitsky had absolutely bored her.

I won’t speak to her for another two days.’]

–

Did Grushnitsky bore her?

Really?

Pechorin is so fucking charming at all fucking times isn’t he, no woman will reject him, he chooses his targets very carefully.

+++

I lay in bed with my back against the wall and the computer on my thighs.

On the screen was the original series of Star Trek.

Kirk had disappeared into parallel space and the crew had to rescue him. But most of the crew thought he was dead. Only Spock still believed.

As the episode continued I briefly wondered if this was the best way to spend my time on this earth, but it didn’t last long. No, this was an okay way to spend time. It wasn’t making me any money, but it did make me feel…what? Happy?

And it wasn’t forever. Things could be figured out tomorrow, not tonight. Or the next day even. It didn’t really matter.

Besides, there weren’t an infinite number of Star Trek episodes. They’d run out sooner or later. And then I’d act.

The episode played on.

I watched zombie-like as Spock and McCoy played a recording of Kirk. It was a video to be shown in the event of his death.

Before the video they argued.

After the video they were silent.

Then McCoy left and Spock stood alone in the room.

Peace and quiet at last.

+++

+++

[‘But there is an unbounded pleasure to be had in the possession of a young, newly blossoming soul.’]

–

He never pursues a weathered target, never confesses to anything that might humiliate himself.

Never.

Romantic honesty.

Head always half turned away.

I despise this man.

+++

Jay sent a message asking me where I’d been, what I’d been doing the last three months.

I replied, ‘Nowhere and nothing. Just watching Star Trek.’

+

The next day Jay wanted to know what I was playing at.

‘What do you mean?’

‘You can’t retreat into Star Trek. Gotta get a job, make cash. Seriously, bats.’

My eyes and possibly my brain took in the words on the screen, rescanned a few times, then replied:

‘I know what I’m doing.’

‘The fuck you do. You’re stagnating, you need friends/life to snap out of it. Trust me, home alone no good.’

I read it then turned off the phone.

+++

+++

[‘I was prepared to love the whole world – and no one understood me – and I learned to hate.’]

–

He still loves the scenery, the slopes of Chechnya.

People can be hateable.

Small and petty.

I’m repeating myself cos there’s not much more to say. Pechorin is relatable but also tedious. ‘I will get bored of you, it’s in my character, I don’t know why’ is okay once but when I just want you to pick up the phone and fucking talk to me…

Did Lermontov really see himself as unique? Isn’t this just a copy of Valmont in some way, as it says in the introduction?

What good’s honesty if it’s always self-romanticising?

Make yourself look like a wretch, wretch.

+++

There were nearly eighty episodes of the original Star Trek.

I clocked eight a day and did nothing else.

It wasn’t clear why, but for some reason it seemed like the right thing to do.

+++

+++

[‘My colourless youth elapsed in a struggle with myself and the world. Fearing mockery, I buried my most worthy feelings in the depths of my heart: and they died there.’]

–

Nihilism is a dead end.

Flowers cannot grow there.

I need them to, because…?

Pechorin is Jay and Kaia, a walking void that you’re never gonna get to the bottom of, no point even trying.

Jay is a fraud, Kaia, the void.

Where is she now?

The French Language Centre?

+++

Spock put his face near the exotic flower and it greeted him by spitting out pollen.

Alien pollen.

Five seconds later, he was a libertine.

Fifteen minutes later, the whole crew was the same.

My room sat silent.

The apartment sat silent too, apart from the wind blowing against the fan in the bathroom. My only remaining fear, someone breaking in through one of the windows, had been dormant for a while. And it was an anxiety more than a fear. Couldn’t be afraid of something more colourful than this. But you could be anxious at seeing someone, a stranger that shouldn’t be there, with a tedious script and tedious violence.

I watched the episode aware that there weren’t many more left.

What would I do when it was over? Days were blank, nights were Star Trek, there wasn’t much money left, I didn’t want to see anyone, even Jay, especially Jay. How many directions were there to take beyond that?

Don’t think about it, I told the darkness holding everything up. I’ll figure things out tomorrow.

On screen, the crew left the ship and Kirk sat alone on the bridge, the only person unaffected by the alien pollen. The last autocrat, floating in that huge metal thing above a planet full of hippies.

Or not a whole planet, there was only one settlement, a farm.

But it didn’t matter. That’s where everyone was. And Kirk was alone with a load of computers and screens, lifeless, sterile.

This doesn’t seem right, I thought, looking at the empty spaces around the man in the mustard yellow shirt. He’s the conventional one, the others are transgressive, impulsive.

I looked at the dark spaces in the room.

Was this the right way round?

+++

+++

[‘I was telling the truth – and no one believed me – so I started lying.’]

–

What truth?

That he doesn’t feel much for anyone, anything?

He does feel, it just has an expiry date of about two days. Maybe he needs to stop hanging around with soldiers. And kidnapping tribal princesses who don’t know anything about the world.

He chooses low targets cos he might be defeated by someone higher?

Jay lies.

Lies with sincerity.

Kai tells the truth.

With sociopathy.

What if…you could go all the way into the centre of nihilism and come out the other side, an optimist?

+++

Another few nights and the original series was done. I thought about watching the modern ones [or more modern, they were still twenty…thirty years old], but countered myself.

It’s not the same, I warned.

I didn’t know why, but somehow it wasn’t the same.

+++

+++

[‘You speak in strange whispers. This is not the way of Landru.’]

–

Notes on Star Trek

[The loneliness of Space]

–

Start with whatever comes up, don’t think about structure/order.

Every planet they go to is mostly unpopulated. There are a few settlements sometimes, or a few rocks and a nasty alien, but most of the time there’s nothing.

What does this mean?

Space really is a frontier.

The planets are undiscovered and a lot of them are derelict/ lonely.

Parallels?

The world is lonely too.

Is it?

Every country is known, every place has been discovered, are there any spaces left?

Yeah, the spaces between people.

7 billion separated psychologies.

Pathologies.

My apartment is empty. No one comes here anymore. No Kaia or Bela or Tomomi the Unready.

If you can’t relate to other people, if you’re not interesting to them or interested in how they think, or what they tell you about how they think, or what you suspect the way they think is, then they become nothing but objects.

Which means you can be alone.

Like Kirk on the empty ship.

But people can still fuck you up, they can be nasty objects, hateable.

–

The purpose of Kirk and the crew

–

Their lives are interesting: they wake up and they literally don’t know what they’re gonna run into that day.

I wake up and I know exactly what I’m gonna run into.

My own fault?

The aliens are sometimes bad, sometimes good.

The aliens I run into are always bad, you might say not, but I know the way they really are, they’re disgusting, even if they’re friendly, they’re disgusting, liars.

Life in Star Trek is exciting.

Life in the 2260’s was exciting.

Life here is not.

What else?

There’s the potential of improvement in the Star Trek universe. You can become superpowered, like Gary Mitchell in the pilot, with his telepathic white eyes. He did turn evil, at last, but the theory part of it is exciting.

And did he really turn evil? They were the ones trying to kill him, and he was superior to them. If I’d been in that episode, I’d have understood.

I don’t want to be superpowered.

That would be bleak.

Just like Pechorin, everything would still turn grey and tedious and-

Star Trek is about society, communism [without detail], a ditching of money, the freedom that fusion power may bring [20 years from now].

It’s a dream, so fucking vague.

There’s no improvement in this world. People are shit, and they’ll always be shit. Capitalism sucks in everything and atomises. The only way to beat it is…to do what?

Isolate myself?

+++

I picked up one of the zines and flicked through it.

It was almost a year out of date, but did that matter? There wasn’t much of it that was time-specific, except the Tomomi Leung/Sundance Film Festival piece, but no one would really care, would they?

Do it, do it, do it, do it, you fucking wretch, I shrieked at myself.

Uh-huh.

I put the zine down and looked at the others.

Forty-four left.

Maybe.

I’d done London, okay, but there were other places.

Next to the pile of my own work was another zine cast adrift. I leaned down and picked it up, realising as soon as I saw the Green Day singer playing scrabble on the cover that I knew this one.

The guy who went to China with Green Day, but not really China, just Hong Kong, and his whole mission, the point of the zine, was to judge his friends, how they’d changed since he’d toured with them twenty years earlier and-

Bored, I sat down and read the first few pages.

Apparently the lead singer of Green Day was an introvert.

And pissed off that other punks hated him

cos he was still a punk

at heart.

I paused and looked at the wall.

Okay, I’m not a punk, I thought,

punks go outside

challenge people

but I don’t think I’m that different.

No, it’s true,

I’m not

I made a zine and put it in the Cross Club,

wrote about fucking messy 19 year olds and

wandering the streets of Hong Kong

at 2am

not even the lead singer of Green Day would do that

not anymore

except maybe the messy 19 year-old bit.

+++

+++

[‘I sometimes despise myself…is that not why I despise others?’]

–

He sees a mirror in others, minus the sociopathy? Is he despising the lack of it or the abundance of it in himself?

I don’t know.

He despises the part that pretends, that is reflected in what he sees of others?

Kaia would know, hermit witch.

+++

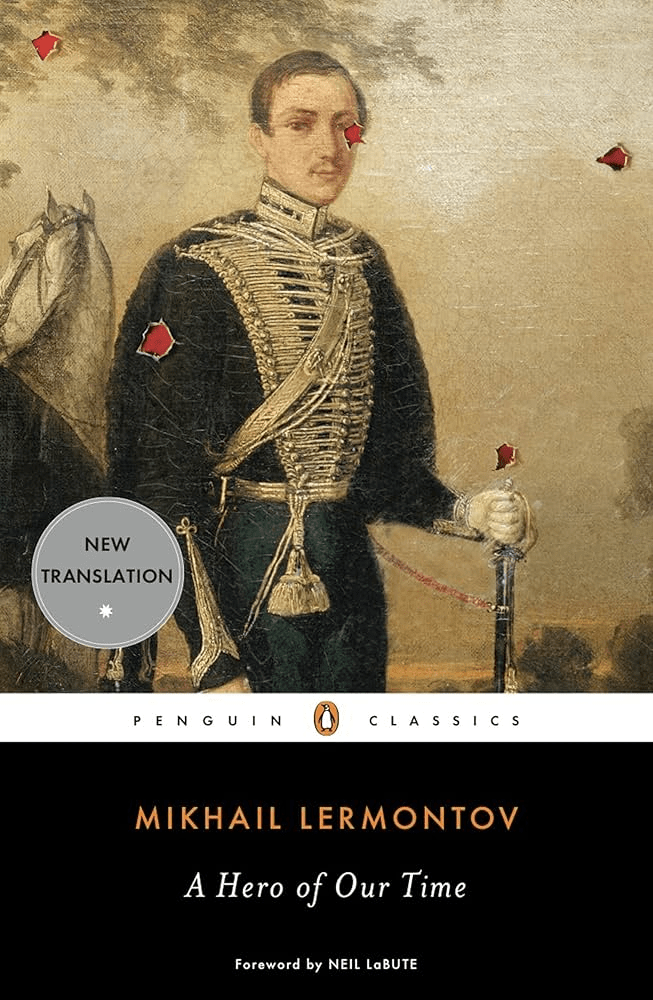

I sat on the bed with A Hero of Our Time by the window, buried beneath Platonov and Haldeman and Heinlein and Tanith Lee.

What was it I wanted to say, I asked the shot-up Pechorin on the cover, what was the point behind it?

I decided ‘nothing’ and went back to the piece of paper in my right hand.

A bank statement.

Bank threat.

Counsellor for the duration.

A durable Lord Byron.

I looked at the numbers and remembered Kaia’s words, her old typed words, ‘I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor,’ then folded the paper into a shitty little airplane and threw it at the wall.

+++

+++

[‘What am I expecting of the future? Exactly nothing, really.’]

–

Enough randomness, here’s what I’m focusing on:

–

1] The worldview of the narrator

2] The idea of transgressive fiction

3] Honesty

–

All the notes I made while reading this before can go at the end, kind of like my version of ‘show your thinking’…

Most of it was shit anyway.

Overview [from memory]:

–

So, the first part of the book, Pechorin’s seduction and discarding of Bela, the tribal princess [At least, I think she’s a princess.]

What actually happens?

Pechorin goes to the Caucasus mountains and serves as a soldier. He meets the princess of a local tribe and manipulates events to get her into his tent [has her abducted by a lackey]. At first she’s mad, but then she loves him. As soon as the change occurs, he gets bored and ignores her. She dies from a stab wound, and he appears genuinely upset [without tears/words, via guilt].

What does it mean?

First of all, the way he captures the princess, or gets her into his bed/tent, this is not the action of a romantic hero [perhaps a Byronic one, a nihilist?] He does not prove himself worthy through action or noble deed, he simply creates the circumstances which lead her to him against her will and, from that point on, dominates her like a predator/warden.

But she still falls for him?

He is charming like a villain, gives her presents, shows indifference. Was this intentional by the author?

–

This thing reads as if it really happened, or the spirit of it at least. Maybe the events are a little too fucked up to be real, but the domination and seduction seem convincing. Was Lermontov this charming in real life? Or is this a fantastical re-telling of what he wished he was?

Why does he ignore her?

He is bored. This makes him a piece of shit, which would be a problem in any other kind of fiction. But as a character he is honest about this boredom. Destructively honest.

–

But is it true honesty?

I’ve met loads of people in real life who claim absolute truth, but they’ve all shown themselves to be liars. Jay says he speaks exactly what he thinks, but he doesn’t. I know he doesn’t. It’s selective truthing. None of it humiliates him. Some of it humiliates others. Like the French girl he fingered on New Years Eve then left to walk back to the train station alone, at half midnight while he looked for new targets at the hostel. And when I called him on it, he told me he was depressed, didn’t know why he did that, she’s better off away from me etc.

And Kaia…she chooses when to be honest and when to lie, and when she’s honest, she’s blindingly honest, so much so that it fools everyone into thinking this is her default setting and she’d never tell a lie about anything, but it’s not true, it’s a posture, she says she’s anti-posture, but I know it’s a posture.

None of it humiliates her.

All the confessions are dark.

Why do people believe their shit?

–

If you think it through, there’s a simple formula. You take Kaia and you look at her life, she spends most of her time alone, which only ever makes a person vindictive, hateful towards the world.

Is this a formula?

–

Okay, forget Kaia, Jay’s a better example. Take his life: he tells me I have to get a job and get myself sorted, but this is conventional reasoning, yet at other times his advice is transgressive, he talks about depression and dissatisfaction with things – where’s the way out, what is the point of all this, I wanna fuck a manic depressive, at least that feels real – but at the end of it all he’s stuck in convention, the way of things.

–

That’s not a formula.

–

But the job thing, that’s true enough. He only wants me to work so I won’t go anywhere and do anything different that might make him feel wretched about his own life.

Fuck him, I’m not going that route.

Work as what? Where?

He’s just scared, scared that I’ll find a different way, and he won’t have the balls to follow.

But what different way?

–

Too much of a tangent, back to Lermontov.

–

The princess story: he ignores her, she dies, he laments. It’s not difficult to understand. He got her, she submitted to him, and it bored him. It doesn’t make him evil, just callous.

–

And his honesty: he tells the guy narrating the first part of the story he doesn’t know why he gets bored so easily. Why does he tell the man and not the princess?

Because the man is outside the play? Or the game?

Pechorin has nothing to lose or gain by telling the man the truth, that he is a sociopath, or a semi-sociopath…a full one?

A total sociopath wouldn’t feel anything at any part of the seduction, and would feel no loss at her death. What afflicts Pechorin is worse than this, it is feeling with a time limit, a “living” within his own head and thoughts that is stronger than actual living.

Can anyone not relate to this?

–

The honesty returns later in the book, when Pechorin becomes evil[er?]. He pursues another woman, a young girl of society, she’s eighteen, I think, and he pursues only because another soldier is after her. It’s a game, and he’s the only one who is one hundred per cent playing.

–

What happens in this part of the book?

–

It’s the main section, and predates the previous stories, at least I think it does. To be honest, the dates still confuse me a little as there’s often a change of narrator, and the main section is taken from Pechorin’s diary. I had it the right way in my head before, but it’s gone now.

–

Anyway, he’s on leave in some kind of resort village, and there’s another soldier who’s a lower rank than him, Grushnitsky, and for some reason Pechorin wants to humiliate him. It starts when the young girl arrives and the other soldier shows his interest in her. From this point on, Pechorin schemes and eventually seduces the poor thing, yet feels nothing for her. He also has a duel with Grushnitsky and shoots him off a cliff, which is a real piece of shit thing to do, but partially excused by the context [Grushnitsky and his second tried to cheat by not loading Pechorin’s pistol].

–

Looking back on these notes, there’s a chance that I’m skimming through this book too fast. And I know I’m repeating myself. Fuck. How long should this thing be?

–

There’s no real purpose to any of it, not really.

–

Would a magazine accept it as a short story? Would they pay me for it?

–

Forget it, stick to the analysis. Got nothing else to do. Even the charities don’t wanna hire me. Not that I want to stand on the street and talk to anyone anyway. What’s the point? Only the nuts stop to talk.

–

Lermontov, Lermontov…

–

Okay, so this part of the story, the part I detailed above, this shows Pechorin at his most amoral. He purposefully sets out to seduce a girl he feels nothing for, and to humiliate another man who has done him no wrong. In fact, the other soldier, Grushnitsky, acts as a friend towards him for most of the story.

What does it mean?

There are layers to this. It’s hard to pick out parts and analyse, but from Pechorin’s perspective, the other soldier is playing the same game as him, yet the difference is he’s only half-playing it, and, crucially, he underestimates the other player. If a man likes a woman then he makes himself aware of any threats or obstacles to his own intentions. The problem for Grushnitsky is that Pechorin disguises his own threat; he doesn’t detach himself from the other soldier and let himself be seen plotting, he does it right next to him, just like Iago, and Valmont, who Lermontov apparently leaned on for the writing of Pechorin [according to the intro].

–

But the thing is, does this game take brains?

I don’t know, I suppose it does. It definitely takes deception and a precise strategy, but couldn’t anyone do what Pechorin does?

I know I could.

Kaia could too, to a supreme degree.

Jay…possibly, if he kerbed the sleaze a bit.

–

Wouldn’t it be good to go back and plant yourself in this story? To stand there and look like a prop but all the time know what Pechorin’s up to, and then, at the last moment, thwart him and fuck him up. To out-Pechorin Pechorin!

–

But what if every man played the world this way?

What if every woman did?

There wouldn’t be any transgressive fiction, no nihilism, as it would be the only ism, nothing to transgress as normal would be something no one would want to transgress.

–

Wouldn’t a world full of Pechorins be a nightmare?

–

Another interesting part of the story is the honesty of Pechorin, or the false honesty?

There is a part of the seduction where Pechorin has got closer to the princess and they’re riding their horses near the village and as the others ride ahead, Pechorin pulls the princess back and tells her how soulless he is and why he’s always struggled to love anyone.

The princess laps it up and pretty soon afterwards wants to fuck him.

Not the princess, Vera.

Vera laps it up and wants to fuck him.

–

So the thrust of this section is: Pechorin reveals himself completely, nakedly to the girl, and obviously no one has ever done this with her before or is likely to again. To a normal man, like the other soldier, Grushnitsky, this degree of honesty would seem to be suicide for his intentions. But Pechorin reveals all. Why?

I know this game well, Jay knows this game well. Reveal your dark soul, and show yourself to be different, fresh even. But it’s artificial. And with Pechorin it’s artificial too. It’s a strategy that hasn’t been wielded before.

Isn’t it?

–

I’ve re-read the passage in the book a few times and I think I’ve nailed down the artifice. It’s the tone, and it’s the details of what he says. He doesn’t reveal the sociopathy as something he’s responsible for, he reveals it as something that’s in him, but beyond his control. ‘I’ve always been this way,’ he says, ‘and I don’t know why.’

Is that true? Is there another level of honesty he hasn’t reached here? If Vera lost interest cos of this confession, would he change tack and confess on a different vector? Is it any of it without design/intent?

I’m not sure anymore.

But no, it is a lie, it has to be. He doesn’t tell her he’s playing the same game with her at that moment, he doesn’t reveal anything that makes him look pathetic. He’s romanticizing himself, playing the pathologically cunt-ish anti-hero, a role that no one else has the wit to play obviously, and it’s fraudulent. Just like Jay and Kaia, it’s selective honesty, it’s a lie, it’s bullshit. Even Lermontov knew it. This whole book, it’s the same game Pechorin’s playing – Pechorin is Lermontov and he’s revealing the game he plays, but there’s another level to it that he’s keeping back, there has to be, no one ever reveals everything, they can’t, I’ve never seen it, it’s-

You reveal everything, truly everything, and the only act left is suicide.

Or complete transgression?

–

Fuck, the sun’s come out.

+++

+++

A Hero Of Our Time has been out in the world for nearly 200 years, look for it in your local library or second hand book shop or whatever’s left when the parasites have stripped us of everything, I will never be a nihilist that way, I refuse.

+++